How the building blocks of life fought to survive in the planet-forming disc 4.5 billion years ago

The basic chemical precursors to life came from space, brought to Earth on asteroids and comets, but how did these precious molecules survive the ferocious environment of the protoplanetary disc?

Where did we come from? It’s a question as profound as the existence of life itself; a longing, deep within us, to know our ancestry, to know the beginning of our story. Carl Sagan spoke romantically of life being made of starstuff, from elements forged within the nuclear hearts of stars and which over four-and-a-half-billion years of evolution self-organised themselves into an assemblage of complex organic molecules from which emerged instinct, cognition and sentience.

It’s true, all of it. And yet, this basic picture leaves huge gaps in our knowledge. How did we get from elements dispersed into deep space to life on a blue planet? New observations of a young planetary system in the process of forming have provided some much sought-after answers.

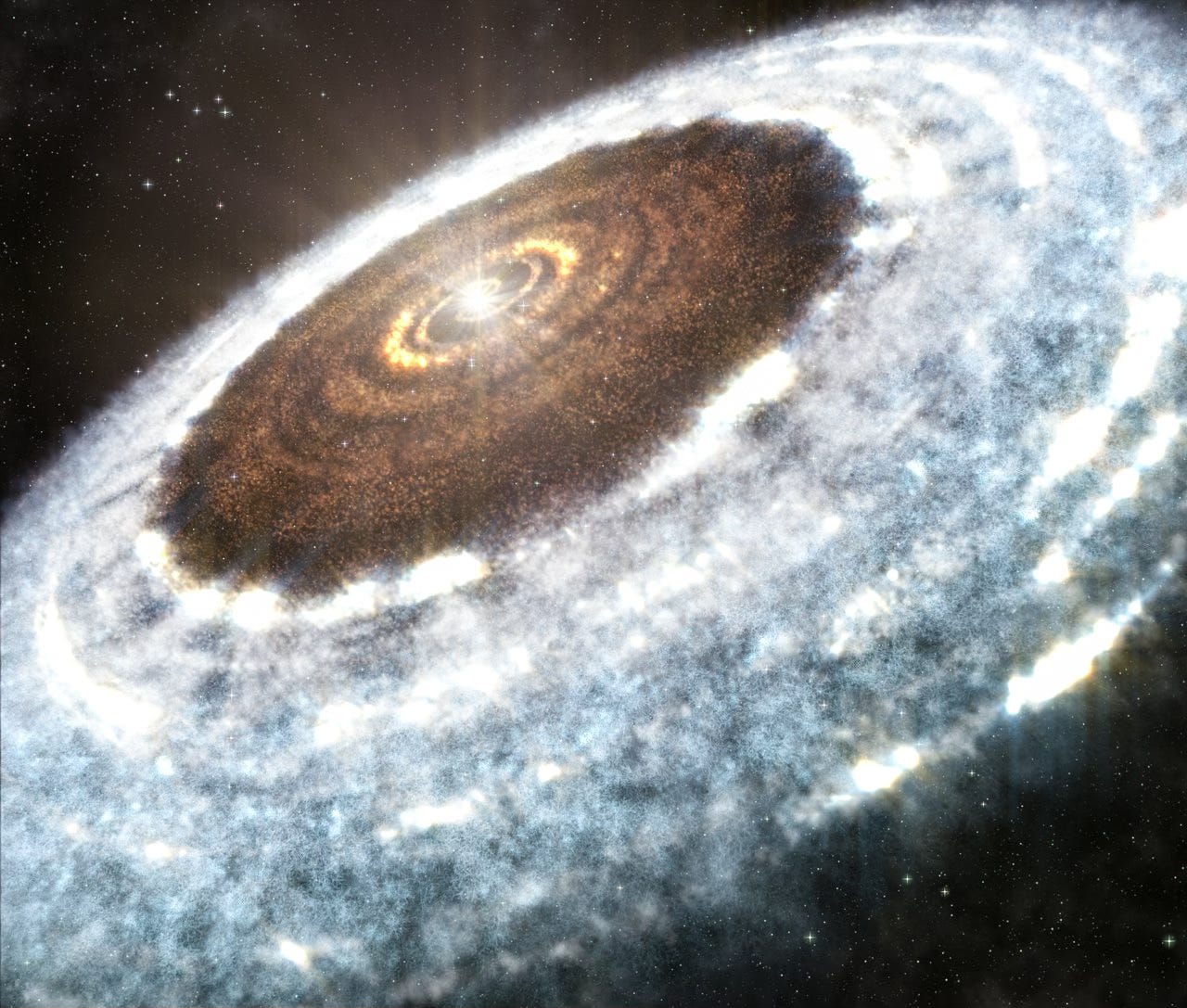

An artist’s impression of the protoplanetary disc around the young star V883 Origins. A similar disc once formed the planets of the Solar System and facilitated the delivery of organic molecules to Earth. Image: A. Angelich (NRAO/AUI/NSF)/ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO).

We don’t yet know what sparked life on Earth, but we do know that our chemical roots, the most basic building blocks of the biological machinery used by everything from the simplest microbe to you, dear reader, can be traced back to space. We know because we’ve found them there.

The stuff of life

Complex organic molecules are molecules constructed from at least five atoms, including at minimum one carbon atom (it’s the carbon that puts the ‘organic’ in organic molecules). The most complex organic molecules related to life are things such as amino acids, sugars, nucleobases, proteins, even DNA and RNA. Our missions to asteroids and comets in the Solar System have discovered complex organic molecules just sitting there, inert, in these bodies that are older than Earth, leftover chunks from the planet-building phase of the Solar System 4.5 billion years ago.

Europe’s Rosetta mission to comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko last decade delivered a little lander called Philae to the comet’s surface, where it identified numerous complex organic molecules including glycine, which is the simplest of the 22 amino acids involved in life (there are more than 500 amino acids known, but most are not utilised by life as we know it). Among other things, chains of amino acids create proteins that function as the body’s workhorses, facilitating our metabolism, our immune system, the management of body tissue, and the catalysis of enzymes.

More amino acids were identified in a sample of material brought back from the surface of the asteroid Ryugu by the Japanese Hayabusa2 mission in 2020, with different reports suggesting the presence of between 13 and 23 types of amino acid, including glycine. And the sample retrieved from the asteroid Bennu by NASA’s OSIRIS-REx mission contained 14 of the 20 amino acids used by life on Earth, as well as all five nucleobases used by DNA and RNA to store and carry instructions that tell cells what to do.

Because these asteroids and comets are primordial, pre-dating the formation of Earth, it suggests that these elements were present in the planet-forming disc around the young Sun and were delivered to Earth after our world formed. In other words, the basic building blocks of life came to Earth from space, whereafter they did whatever magic they do to give birth to life.

So the question becomes, how did these complex organic molecules come to be in the planet-forming disc that eventually became the Solar System?

Perhaps they were created in the planet-forming disc when it was still a swirling morass of gas and dust, but Kamber Schwarz, who is an astrochemist at the Max Planck Institute of Astronomy in Heidelberg, Germany, tells me that there’s a problem with that idea.

“To get the required abundances would take longer than the typical lifetime of a disc, which is about three million years,” she says. The inference is clear; at least the smaller complex organic molecules must have originated from somewhere else before they found themselves within the protoplanetary disc to allow enough time for the larger complex organic molecules to form.

Molecular magic

Go back far enough in time, to before 4.6 billion years ago, and you will find that every atom inside the Sun, the planets, and you and me, resided in a vast cloud, light years across, consisting of molecules of gas. The galaxy is filled with such clouds. Many remain cold and dark, but others have been triggered into action. Perhaps a close passage by another molecular cloud as they became bunched up in the over-densities that form our Milky Way Galaxy’s spiral arms disturbed those clouds, prompting gravitational collapse. During this process the collapsing cloud fragments into many smaller clumps, each clump condensing into a star or stars. The Orion Nebula is the best example of this in the night sky. It’s how our Sun was born.

The Orion Nebula is a gigantic molecular cloud inside which pockets are undergoing gravitational collapse to become new stars. Image: NASA/ESA/M. Robert (STScI/ESA)/Hubble Space Telescope Orion Treasury Project Team.

Complex organic molecules enrich these molecular clouds, harboured on icy grains of dust where they can react with other molecules, combining and increasing their molecular complexity. Hydrogen is particularly good at this, its low mass meaning that it finds it easier to jump around and latch onto other atoms and molecules, hence why so many organic molecules are hydrocarbons, containing atoms of hydrogen and carbon.

Planetary systems inheriting at least some of their complex organics from frozen storehouses in molecular clouds is a nice idea, and solves the problem of not having enough time for a planet-forming disc to produce them from scratch, but there’s a really big problem with this.

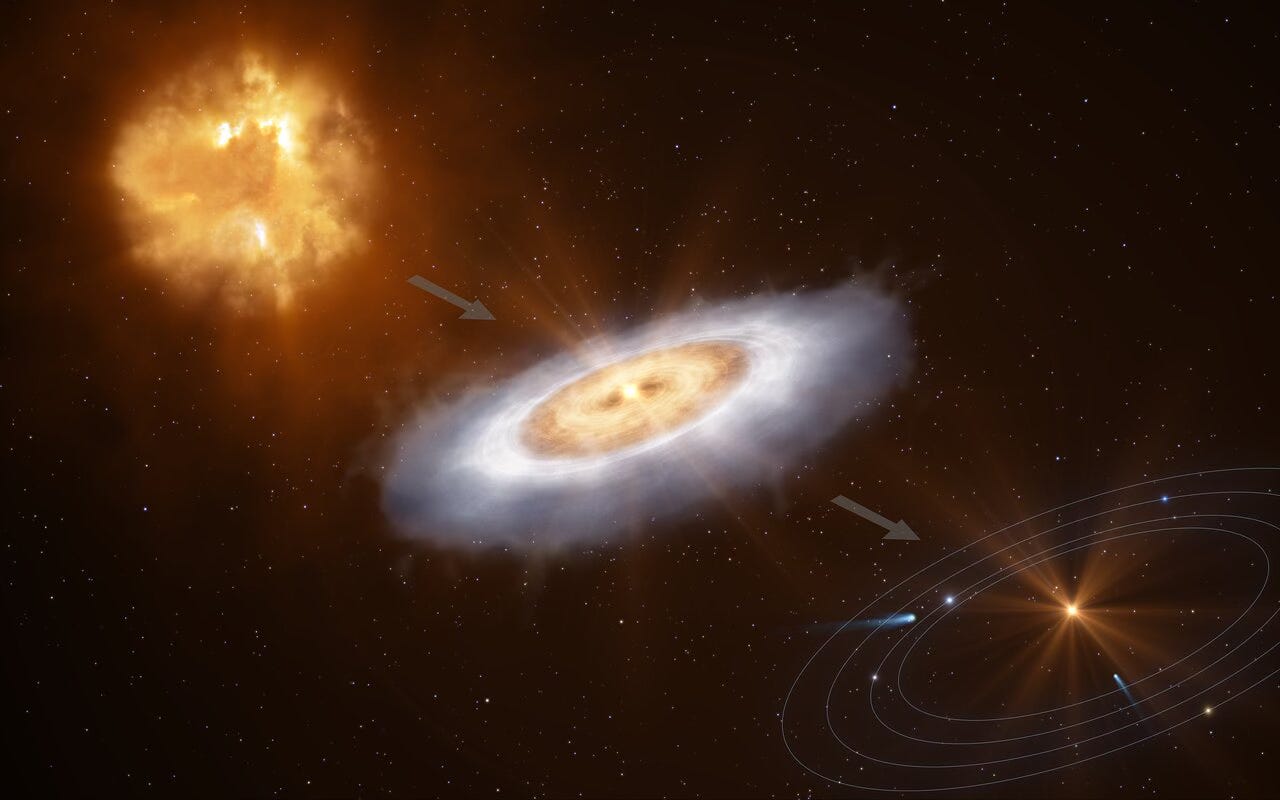

Birth of a planetary system: the depiction of the progression from a collapsing cloud of molecular gas into a protostar ringed by a protoplanetary disc, to a mature system of planets. Image: ESO/L. Calçada.

Imagine a clump within a collapsing molecular cloud. Gas is infalling to the centre of the clump, gradually increasing the density at the heart of the clump to eventually ignite nuclear fusion reactions and give birth to a fully fledged star, or stars. The gas is infalling at different rates from all directions, and sets the protostar and the material accreting onto it spinning. The rotating material around the protostar flattens into a disc, which is the precursor to the planet-forming disc, all the while matter is still infalling.

Except, imagine what happens when a huge mass of gas containing delicate and complex organic molecules slams down into a tangentially rotating disc of gas.

“There’s a shock at the boundary where they meet,” Schwarz tells me. “We think of it as a centrifugal barrier – it’s like two cars travelling in different directions that hit each other.”

In theory, the shock should smash apart the complex organic molecules falling onto the disc from the cloud. In this case the disc wouldn’t inherit any of the complex organic molecules and would have to rebuild them from scratch. But there isn’t enough time for the disc to not only reassemble them but also generate further reactions that form the amino acids, nucleobases, sugars and possibly proteins that wind up in asteroids and comets. That’s because the clock is always ticking on a planet-forming disc – once a protostar has gained enough mass, and the density and temperature in its core is great enough, nuclear-fusion reactions switch on and the sudden release of fusion energy from the star is enough to blow away any gas and dust in the disc that has not yet become accumulated within a planet, moon, asteroid or comet.

It’s a paradox. A planet-forming disc isn’t around long enough to build from scratch the sufficiently complex organic molecules that end up in asteroids and comets, and yet the complex organic molecules that the disc should inherit from its parent molecular cloud to give its organic chemistry the required head start should, in theory, be destroyed. Both things cannot both be true, and now Schwarz’s team, led by Schwarz and her PhD student Abubakar Fadul, have proved it, showing that there is no paradox.

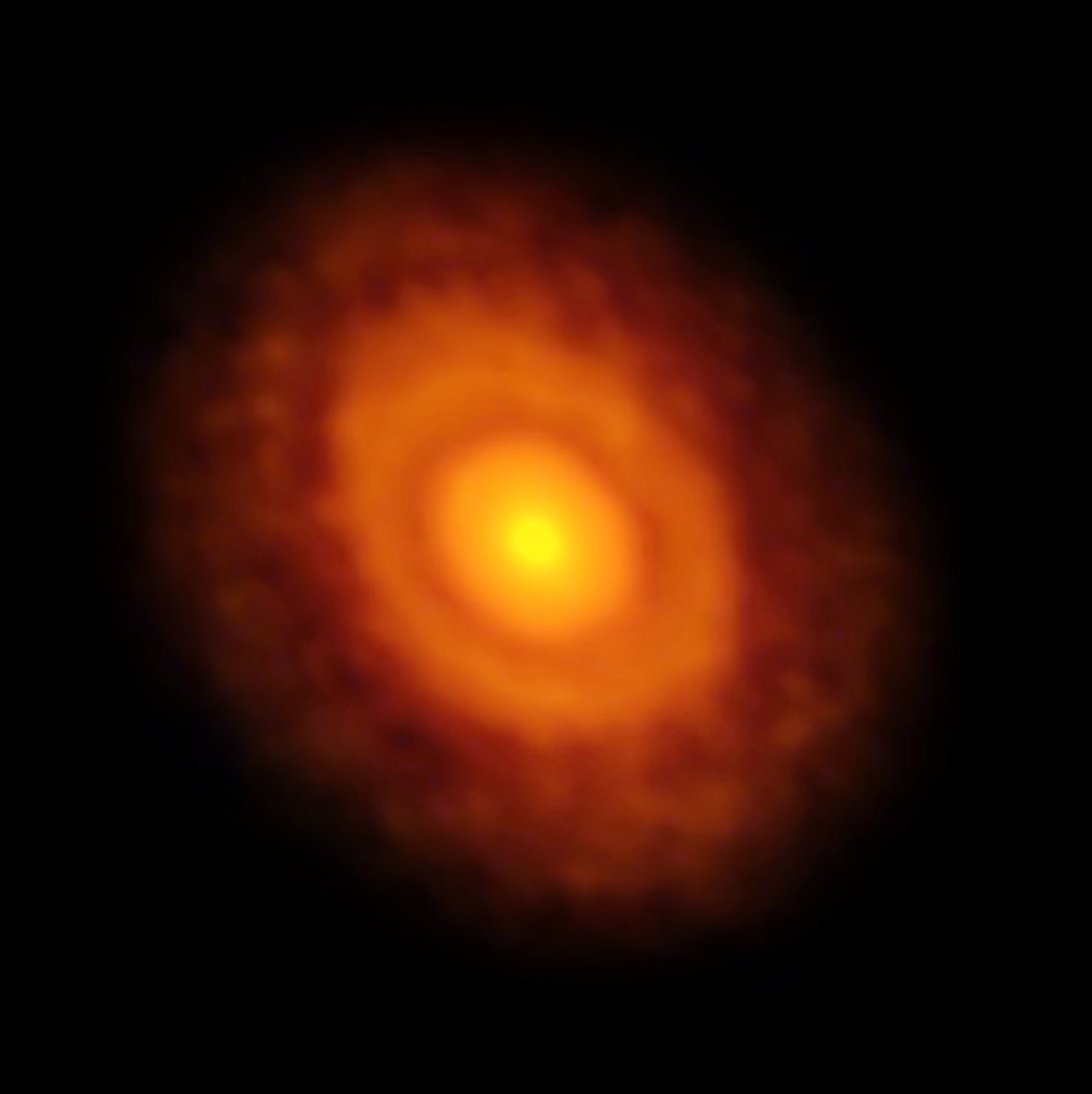

ALMA’s submillimetre radio image (in false colour) of the protoplanetary dust disc encircling V883 Orionis. Image: ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO)/L. Cieza.

Shock survivors

Using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array – better known as ALMA – in Chile, the team of astrochemists probed the protoplanetary disc around a young star known as V883 Orionis, seen in the constellation of Orion, the Hunter. Previously, in 2023, ALMA detected water vapour in V883’s disc. Now, Schwarz and her colleagues haven’t just been looking for complex organic molecules in the disc, but also for how abundant they are compared to their abundance in typical molecular clouds. To gauge their abundance, they measured the strength of their signal relative to the presence of methanol, which is detected in significant amounts in both molecular clouds and planet-forming discs, making comparisons easier. Because the disc is warm, the ice on dust grains would have sublimated, releasing the complex organic molecules as gas that ALMA can detect.

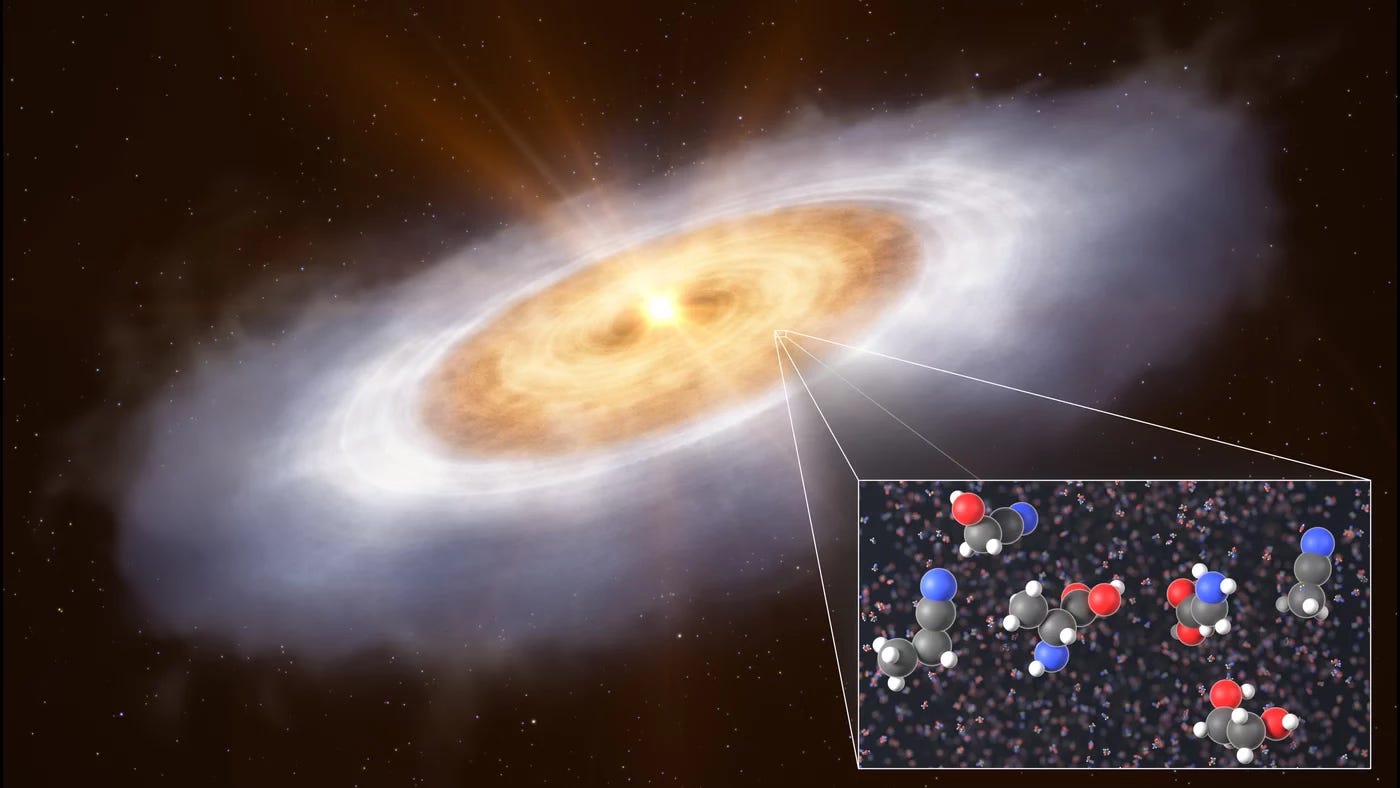

The team found high abundances of 17 different complex organic molecules, including ethylene glycol, which is a precursor to sugars, and glycolonitrile, which is a precursor to the amino acids glycine and alanine – it would take just one or two more steps to form those amino acids. Other complex organic molecules could also be lurking within the disc, their signals not strong enough to disentangle from the disc’s spectrum.

To add further intrigue, their abundances are even higher than in molecular clouds.

“The timescales that it takes to form these molecules are typically pretty long, so because of that we think the disc inherited some of these complex molecules from the cloud and then continued to make additional complex molecules to increase their abundance,” says Schwarz.

Another artist’s impression of the protoplanetary disc around V883 Orionis. Inset is a depiction of the complex organic molecules that have survived the infall into the disk from the molecular cloud. Image: ESO/L. Calçada/T. Müller (MPIA/HdA).

It is compelling evidence that complex organic molecules are not destroyed by the shock of hitting the rotating disc. Somehow, they survive, and what’s more, they propagate. Young stars are tumultuous, prone to bursts of energy and ultraviolet flares, but while ultraviolet can photodissociate – that is, break apart – molecules, it can also ionise them, stripping them of an electron, an act that prompts the resulting ions to go looking for another electron, often attached to another molecule, to replace the lost one. Hence, molecules can grow more complex in a careful balance between destruction and creation.

How these molecules survive the shock of impacting with the rotating protoplanetary disc is still unclear, but the reasons why are not necessarily important right now. What is most pertinent to this discussion is that they seemingly can survive, and their endurance gives the prebiotic chemistry in the disc the head start it needs to form much more complicated organic molecules such as amino acids and, perhaps, even proteins in the limited time during which the disc exists. (While we haven’t found any proteins in space yet, it is expected that one day we will.) Once formed, these complex organic molecules wind up inside asteroids and comets, and are then delivered to planets such as Earth where conditions are ripe for the chemistry to keep developing and growing increasingly complicated, until one day raw abiotic chemistry makes the transition into biochemistry and life.

How that happens is a story for another time, or indeed another book, one that I’m currently working on and which should see publication in the latter half of 2027. Look out for further book updates and stories based on this mystery of life on Earth in future articles on this Substack.

Thanks for reading, and a special thank you to Kamber Schwarz for her help with the article and a fascinating conversation.